Shipwrecked Cargoes

Tuesday, 03.02.15, 07:56

Sunday, 01.10.17

:

Avshalom Zemer

More info:

04-6030800The Mediterranean, especially the eastern basin, is known as the cradle of shipping in the western world, because of its nearness to those lands where the cultures and states of man began at the dawn of history. This is where the necessity and possibility of barter and trading started between the various cultures. We have evidence from the beginning of the 3rd millenium BCE of the trading vessels that sailed the Mediterranean Sea.

The cargo of such a vessel might weigh as much as 100-500 tons. Despite the limitations imposed by the simple square sail, these craft were able to sail from Egypt to the frontiers of the northern shores of Lebanon. Transport by land was much more costly, because loading 100-500 tons onto donkeys or mules would require more than 5000 animals, and the same number to accompany them. Such a caravan would take two or three months to reach its destination. Obviously, as international trade increased, the preference was for maritime transport.

Conditions in the Mediterranean are better for shipping than in the other oceans of the world, mainly because of lack of tidal fluctuations. Secondly, there are calm weather conditions throughout the summer months, good visibility of the shore by day and of the stars at night, and relatively stable winds. All these assisted seafarers to find their way, whether along the coast or in mid-ocean, to their destinations.

In antiquity, setting sail depended on weather conditions in all seasons. Winter was the time of the "mare clausum" - the closed sea - to the Romans, because of storms and suddenly veering winds. At such times trading vessels and smaller craft remained anchored in the harbours. Spring and autumn were thought to be less hazardous. Courageous seamen put to sea from the beginning of March until mid-November, even though the preferred season was from the end of May until mid-September, when the winds were favourable - i.e. stable and not too strong. Currents were also an important consideration when planning a voyage, since most of the Mediterranean currents flow anti-clockwise.

The coast of Israel extends for about 180 kilometres ( from Rosh Hanikra in the north to Rafiach in the south) along the route between the sandy shores of Africa and the indented coast of Europe with its many islands. Haifa Bay is comparatively large, exposed to winds from all directions, so that there is no protection or shelter for shipping against the storms that rage along the entire coast. Storms which burst without warning, lack of shelter, and the limited manouevreability of the early sailing ships were all conducive to the fact that a ship in distress could be dragged from its moorings and sink.

The ship then capsized, and was abandoned by its crew struggling to reach the shore, after which the vessel broke up, and parts of it fell to the ocean floor, where they became covered with a layer of sand. After the storm subsided, part of the cargo was retrieved, and the ship's timbers that had been cast ashore were collected and used by the local inhabitants or by the survivors. After a few years, all that remained were remnants of the hull, and heavy objects that had sunk into the sand of the sea-bed, silent witnesses to the catastrophe. Because of the large number of vessels sailing along the coast, and the increasing number of wrecks, the coastal waters of Israel are a kind of gigantic graveyard for ancient ships.

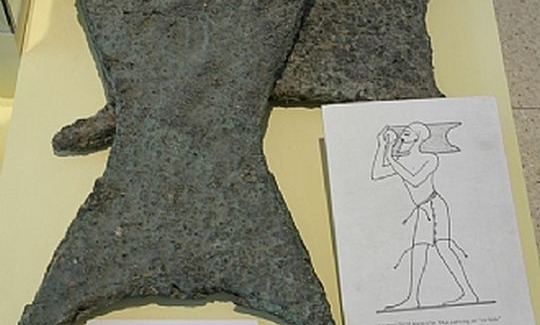

Rich and varied findings are discovered at the site of a wreck; parts of the vessel itself, items from the cargo, the crew's personal effects. The timbers are usually found in anchorages or harbours that are closed and protected, while on the open beaches we often discover metal artifacts that have survived the storms. At the site of the wreck itself, many items of the cargo are found, but we can also assume that much was already removed in antiquity.

At archaeological sites on land we find strata of the settlements of the place and, in many instances, buildings have been "recycled", as have raw materials. This makes it difficult, sometimes impossible, to identify when they were first in use. The virtue of underwater discoveries is that all the items found with a wreck have the same last date of use - they are the contents of a specific vessel which sank at a specific moment in time. Some of them are found in their original condition. The largest cargoes of ingots have been retrieved from the sea. They are rarely found on land because as soon as the metal reached its destination it was cut up and made into implements and articles of all kinds.

Drastic geomorphological changes that have occurred during recent decades, as a result of man's interference with the shoreline (The Aswan Dam, harbours, marinas, etc.), and new diving equipment available to everyone, have enabled discovery of remains which have been lying on the ocean bed for millenia. Thanks to developments in underwater archaeology and the Israeli underwater surveys, our knowledge of the history of Eretz Israel continues to accumulate. These findings present another aspect of the reciprocal connections between the coastal cities of Eretz Israel and other countries and cultures of the Mediterranean, the maritime links in early times, including the types of merchandise carried from place to place. These finds also help us to reconstruct how the seafarers lived, and the types of craft in which they sailed in the various eras.